Front Rudder – by Mark Reid

America’s Cup, American History

As we approach the 4th of July holiday this year, it is important to remember all that we are grateful for. First and foremost, how fortunate we are to live in the United States of America where our forefathers laid down the first vestiges of the right to freedom and independence.

It is mindful to also recognize that like our celebration of Memorial Day, on this holiday as well many American men, women, and races of all colors fought, died or were wounded for our ways of life since the beginning of our republic.

In a parallel way, yachting’s America’s Cup is a timeline of American history. Over the course of the Cup, many of the American defenders have carried names with a ring of patriotism like Columbia and America Cubed. Dennis Conner stuck on that theme in a big way with Freedom, Liberty and Stars & Stripes. Ted Turner, who defended the Cup in 1977, came back to defend his title in 1980, while launching a novel concept in television news. This was a 24-hour network called CNN, which changed the way many of us view and watch news.

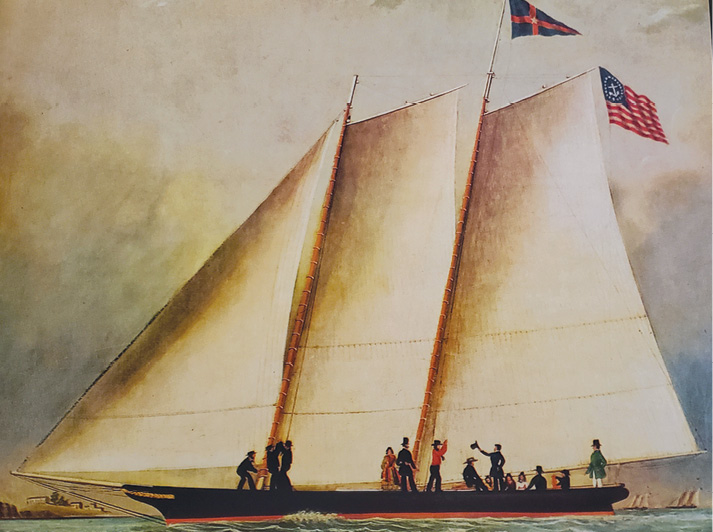

But the original contest for the Royal Yacht Squadron Cup or the One Hundred Guinea Cup, took place off England’s Isle of Wight in 1851. The yacht, America, won and dominated the event to such an extent that Queen Victoria was said to ask, “Who’s in second?” In which she was told, “You’re Majesty, there is no second!” The America’s Cup was held in Britain in 1848 during the age of Queen Victoria by the prestigious Garrard Company. The Cup itself is a very ornate hollow sterling silver gilt ewer, that has been layered over the years to include recent winners and defenders of yachting’s most prestigious event. It was originally called the Royal Yacht Squadron (RYS) Cup, and was purchased off the shelves by Henry William Paget of Anglesey, who donated it to the RYS for its annual regatta around the Isle of Wight. 1851 was a regal year for Great Britain with the Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of all Nations, and the opening of the Crystal Palace. The palace is a massive cast iron and glass building in Hyde Park and was constructed to house the great exhibition where exhibitors from around the world gathered to display the latest technology of the Industrial Revolution. The exhibition was organized in part by Prince Albert.

Aboard America was Commodore John Cox Stevens, who later with fellow members of the New York Yacht Club (NYYC) in an act of conveyance presented the trophy to the club in an 1857 charitable trust as a perpetual challenger’s trophy. Members included financier James Hamilton, Alexander Hamilton’s son and George Schuyler’s father-in-law. Schuyler drafted the wordings of the America’s Cup Deed of Gifts in 1857, 1880 and finally in 1887.

After finally getting his race and wagers in place, Stevens’s America won the contest against the 18 British cutters, schooners and yachts. The America’s Cup trophy was named after the yacht.

The defense of the America’s Cup took place in the summer of 1870 off Staten Island in New York City as the schooner, Magic, won a fleet race against the British challenger, Cambria. America’s Cup historians have now reclassified that series as a Deed of Gift match because of the many interpretive resolutions that were enabled by the two parties in order to come to terms. The yacht, America, which had spent part of the Civil War as a Confederate Navy blockade runner also sailed in the race. The NYYC moved the regatta from New York City to the exclusive resort community of Newport, Rhode Island in 1930.

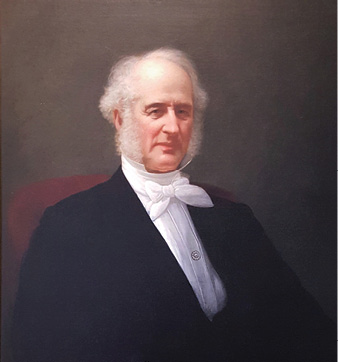

George Lee Schuyler

The trust that George Lee Schuyler placed in his associates, family, friends and ultimately unto New York Yacht Club, as the last surviving member of the American Syndicate, the sailing team that won the infamous yachting trophy some 36 years earlier off the Isle of Wight against the best that Great Britain could offer at the time, has offered an unwavering conviction. In that trust, his written words and deeds would further transcend generations of yachtsmen that would ultimately survive the tests of time and technology.

What has been inherently defined over years and multiple challenges to the weathered old document from 1887 is the author himself. What words, foresight and a damned grand amount of legal clarity was poured into his third attempt to rectify concerns for the past, present and future custodians of the America’s Cup. It was his third and final attempt at a lasting Deed that provided the staying power Schuyler desired and it showed when it came to carving out a document, or negotiating terms. He was as shrewd and astute as an entrepreneur, with lawyerly inclinations.

He served as an acronym, and was born to privilege and persuasion from one of America’s founding families and marital dynasties. Schuyler forged a lineage that George Washington could have had if it were his bloodlines, but it was the Schuyler’s and Hamilton’s.

His grandfather, Major General Philip Schuyler, was a United States Senator from New York, and was succeeded by Aaron Burr. He was married to Catherine Van Rensselaer and Angelica Schuyler Church. Their children were Elizabeth Schuyler Hamilton, Margarita Schuyler Van Rensselaer and Catherine Van Rensselaer Schuyler Malcolm.

George L. Schuyler, through all his business interests in finance, railroads, defense contracts and shipping was a consummate fixture at the Yacht Club’s regatta events. Not as the Commodore or President, but as a referee, measurer and race committee member.

It was Schuyler’s idea that the America’s Cup should become an international trophy, and he was convincing in his discussions with the remaining syndicate members. On July 8, 1857, he drafted the original conditions on which the Auld Mug could be challenged for as a perpetual sailor’s trophy between friendly countries.

Contrary to popular belief and America’s Cup historical accounts, Schuyler did not miss crossing the Atlantic to sail with his yacht, America, because of business interests. Instead it was to help care for his dying mother, and build a summer bathhouse by the beach at their home in Dobbs Ferry for his children.

While NYYC Commodores John Stevens and James Hamilton were wining and dining with English Royalty after America’s victory for the Royal Squadron Cup, Schuyler was home toiling in the boiling August heat, knee deep in mud working on finishing his summer project. In the years after winning the America’s Cup, Schuyler struggled with issues involving his half-brother, Robert, and business partner who had secretly defrauded Cornelius Vanderbilt out of millions of dollars of worthless stock in the Illinois Central Railroad, in a massive Wall Street scandal. One of the railroad’s chief lawyers, Abraham Lincoln, was a young rail splitting congressman from Springfield, Illinois. In 1853, Robert Schuyler was president and transfer agent of the New York and New Haven Railroads, which issued some $2 million in unauthorized stock.

This was America’s first large-scale stock fraud, and its discovery burst like a bombshell over the Eastern establishment. Schuyler had been president of five railroads, helped develop several more and was known as America’s first railroad king.

By 1850, more than 9,000 miles of railroad track crisscrossed the country, predominantly in the Northeast. But railroads were expensive to build, averaging around $30,000 a mile. Locally raised capital built some early short lines, but longer routes needed financing from Wall Street or London.

In the early spring of 1853, the steamer, Independence, of the Vanderbilt Line, which was recently purchased by the Schuyler brothers from Vanderbilt himself unfortunately sank on a voyage from San Juan del Sud, Nicaragua to San Francisco. The steamship was off the south point of Margarita Isle, Venezuela, and within several hundred yards of shore when she struck a rock, and immediately began to fill with water. The accident occurred during the early morning hours. Of the 415 passengers that were on board, 158 were lost by drowning or burning to death in the fire.

Eventually, the survivors were rescued by local whalers anchored at nearby Magdalena Island. The resulting litigation Quimby V. Vanderbilt led to many changes in the existing maritime passenger laws of the time.

Schuyler’s father-in-law, James Hamilton, followed in his own father Alexander Hamilton’s footsteps in crafting banking policies in several administrations, including Andrew Jackson & Martin Van Buren, at a crucial time in our country’s infancy.

Schuyler was extremely close with his father-in-law, marrying his other daughter when his first wife Eliza passed away. He and Hamilton were principles in the Yacht America Syndicate, in addition to being co-founders of the New York Yacht Club. Schuyler had three children, Louisa, Georgina and Phillip. Louisa worked tirelessly her entire life in charitable, benevolent causes including seeing to the health and welfare of soldiers in the Civil War. She founded the Bellevue School of Nursing in 1873. Georgina, a forceful voice in New York society helped raise funds for the Statue of Liberty, and eventually had the poem “A New Colossus,” by her friend Emma Lazarus, inscribed at the base of the statue. Philip served on many race committees with his father, who undoubtedly had a hand in the third and final draft of the Deed of Gift. Philip was tragically killed in a train crash that also killed Samuel Spencer, the president of Southern Railways.

Schuyler achieved the rank of colonial in the army, and served his country with honor at the outset of the Civil War, travelling to Europe at great peril to purchase arms and weapons for the Union Forces. While there, his mission was certainly shrouded in secrecy, in order to evade and outmaneuver confederate spies like Caleb Haney who was abroad with similar tasks for the South. He also was on hand during the infamous New York City draft riots in 1863 to lend command assistance to army troops seeking to help bring the city under control.

Eliza Hamilton Schuyler corresponded throughout the war with William Seward, Lincoln’s powerful Secretary of State. On her deathbed in 1863, she wrote powerfully to him, “you have preserved the inevitable laws of human nature and of God’s progress, seeing the end from the beginning that the abolition of slavery was accomplished.”

In 1887, Schuyler’s ruling in the Thistle Measurement dispute led for the most part to his final rendering of the Deed later that fall.

The Schuyler and Hamilton families were also intertwined in a variety of profound ways with another prominent New York family as well. It is with a certain irreverence that the Reverend Benjamin Moore (1748-1816) almost slipped through the pages of our colonial American history. Like a canvass of colloquialism, Reverend Moore would play an integral role in the way religious leaders shaped our young republic.

If not for his intercession at the behest of the mortally wounded Alexander Hamilton or with a touch of irony, being the father of the infamous Christmas poet, Reverend Moore would have remained a testament to anonymity.

In 1776, at the onset of the American Revolution, he was assistant rector at Trinity Church and acting president at Kings College where he was a Professor of Philosophy and Language. Under his tutelage there would be three of the principal framers of the United States Constitution, John Jay, who later became the first Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, Gouverneur Morris and most famously, Alexander Hamilton.

Reverend Moore participated in the first inauguration in NYC at services that were held at Trinity Church on April 30th, 1789. (Note: Trinity Church is located two blocks from where the World Trade Center used to stand. The church became waylaid in the ashes and soot that terrible day.)

He reassumed his duties as the assistant rector at Trinity, and became Professor of Logic & Rhetoric at the newly renamed Columbia University. New York City became the nation’s first capitol. President George Washington and his wife, Martha, were in attendance at Trinity Church on a regular basis. Martha and Moore’s mother-in-law, Mary Stillwell Clarke, were the best of friends.

Reverend Moore would become the third president of Columbia University. On Sept 11, 1881, he was consecrated as the Episcopal Archbishop. Bishop Moore would assume one of the most powerful positions within that denomination. The Protestant Episcopal Church of America had been rechartered in 1783 from the Tory controlled Anglican Church of England.

This leads us to the events of July 11th, 1804, and the tragedy that took place in the small town of Weehawken, New Jersey. The impact of the event still resonates today. The sharp political differences that brought Hamilton and Aaron Burr, the vice president of the United States, both members of the Federalist Party to duel, still divides our nation and almost crushed it in its infancy.

In the infamous duel between Burr and Hamilton, which ultimately led to the former’s death, Bishop Moore was called upon to give last rites to his mortally wounded star pupil. At great risk to his own circumstance given that dueling, he was considered an abomination by the church. But where the America’s Cup parallel comes in was Hamilton’s son, James. George L Schuyler’s father-in-law became one of the founding members of the New York Yacht Club in 1845, and a member of the America Syndicate six years later. In fact, it was from James Hamilton’s reminisces that much of the Royal intrigue from Queen Victoria and Prince Albert was documented after America won the Cup.

Of course, it was Moore’s son, Clement, an avid yachtsman as well who travelled in different social circles from Hamilton. He had a joint part to play in a pivotal moment in American history which drew them together. This also led to the first few words of Clement Clarke Moore’s legendary trifle, ‘Twas the night before Christmas when all thru the house, not a creature was stirring not even a mouse…

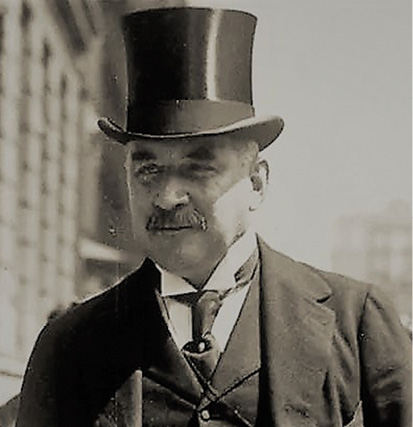

JP Morgan

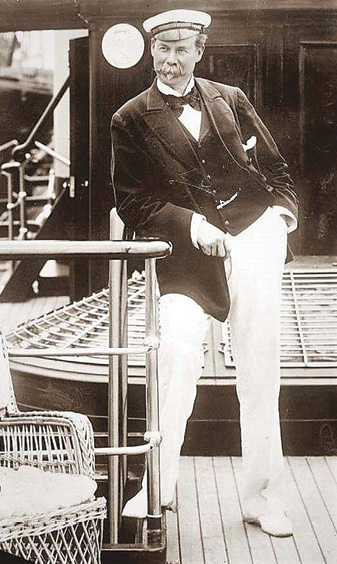

John Pierpont Morgan Sr. (April 17, 1837 to March 31, 1913) was an American financier and banker who dominated corporate finance on Wall Street throughout the Gilded Age. Morgan’s private yacht, Corsair III, was designed and built in 1899 by T.S. Marvel in Newburg, New York, and was designed by J. Beaver-Webb. She was 304-feet overall in length, 33.5-feet in beam and her draft was 16-feet. She was completed in time for the 1899 America’s Cup. Since Morgan was commodore of the New York Yacht Club at the time, she became the Flagship for the club. He also owned the yacht, Columbia, which successfully defended the America’s Cup in both 1899 and 1901.

Corsair III was probably the most famous power yacht of all time, and when asked how much she cost, J.P. Morgan replied with the famous quote “If you have to ask the price you can’t afford it.”

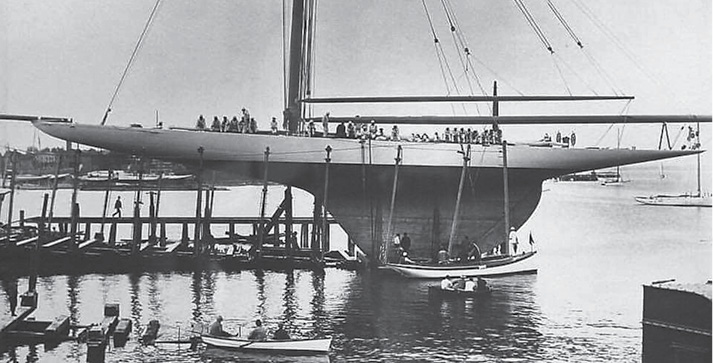

Columbia was built in 1899 for the America’s Cup races. She was the defender against British challenger Shamrock, as well as the defender of the Cup in 1901 against Shamrock II to defend the Auld Mug trophy. She was a fin keel sloop, designed and built in 1898 by Nathanael Herreshoff and the Herreshoff Manufacturing Company for owners J. Pierpont Morgan and Edwin Dennison Morgan of the New York Yacht Club. Columbia had a nickel steel frame, bronze hull and steel mast.

Columbia was launched on June 10, 1899, and easily won the elimination trials against the rebuilt former defender, Defender. Skippered by Charlie Barr, she won all three races against Shamrock in the 1899 America’s Cup.

In 1903, Columbia was refitted with the hope of being selected for a third time, but she was badly beaten in the selection trials by the yacht Reliance.

Columbia was broken up in 1915 at City Island and sold for scrap to Henry A. Hitner and Sons of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Today the mast sits in the Forest Hills Gardens neighborhood of New York City in a park known as “Flagpole Green.”

Morgan spearheaded the formation of several prominent multinational corporations, including U.S. Steel, International Harvester and General Electric. He and his partners also held controlling interests in numerous other American businesses, including AT&T, Western Union and 24 railroads.

Due to his financial dominance, Morgan came to wield enormous influence over the nation’s lawmakers and finances. During the panic of 1907, he organized a coalition of financiers that saved the American economy from collapse.

Morgan was born and raised in Hartford, Connecticut, where he successfully marketed a large part of William H. Vanderbilt’s New York Central holdings in 1883. The Federal Treasury was nearly out of gold in 1895, at the depths of the panic of 1893. Morgan had put forward a plan for the federal government to buy gold from his and European banks, but it was declined in favor of a plan to sell bonds directly to the general public to overcome the crisis. The episode saved the Treasury, but hurt President Grover Cleveland’s standing with the Democratic Party, and became an issue in the election of 1896 when banks came under a withering attack from William Jennings Bryan. Morgan and Wall Street bankers donated heavily to republican William McKinley, who was elected in 1896 and re-elected in 1900. He began talks with Charles M. Schwab, president of Carnegie Co., and businessman Andrew Carnegie in 1900 with the goal of buying Carnegie’s steel business, and merging it with several other steel, coal, mining and shipping firms. After financing the creation of the Federal Steel Company, he merged it with the Carnegie Steel Company in 1901, and several other steel and iron businesses including William Edenbirn’s Consolidated Steel and Wire Company. These companies formed the United States Steel Corporation.

In 1901, U.S. Steel was the world’s first billion-dollar company, with an authorized capitalization of $1.4 billion. It is much larger than any other industrial firm, and comparable in size to the largest railroads.

An avid yachtsman, Morgan owned several large yachts. The first was the Corsair, built by William Cramp and his sons and launched on May 26, 1880. He was scheduled to travel on the ill-fated maiden voyage of the RMS Titanic, but canceled at the last minute, choosing to remain at a resort in France.

The White Star Line, which operated Titanic was part of Morgan’s International Mercantile Marine Company, and Morgan was to have his own private suite and promenade deck on the ship. In response to the sinking of Titanic, Morgan purportedly said, “monetary losses amount to nothing in life. It is the loss of life that counts. It is that frightful death.”

The Vanderbilt’s

Cornelius Vanderbilt (May 27, 1794 to Jan 4, 1877) was an American business magnate who built his wealth in railroads and shipping. Nicknamed “The Commodore,” he is known for owning the New York Central Railroad.

In my own family’s history, it was Vanderbilt and Schuyler who ran their railroads right through their palatial pastoral estates in Chelsea, turning it from an elegant blue-blood neighborhood to a blue-collar working-class industrial part of New York in less than a generation.

At the age of 16, Vanderbilt decided to start his own ferry service. According to one version of events, he borrowed $100 from his mother to purchase a periauger (a shallow draft, two-masted sailing vessel) which he christened the Swiftsure. He began his business by ferrying freight and passengers on a ferry between Staten Island and Manhattan.

On Nov 8, 1833, Vanderbilt was nearly killed in the Hightstown rail accident on the Camden and Amboy Railroads in New Jersey. Also on the train was former President John Quincy Adams.

When the California gold rush began in 1849, Vanderbilt switched from regional steamboat lines to ocean-going steamships. Many of the migrants to California, and almost all of the gold returning to the East Coast went by steamship to Panama, where mule trains and canoes provided transportation across the isthmus. The Panama Railroad was soon built to provide a faster crossing. Vanderbilt proposed a canal across Nicaragua, which was closer to the United States, and spanned most of the way across by Lake Nicaragua and the San Juan River. In the end, he could not attract enough investments to build the canal, but he did start a steamship line to Nicaragua.

In 1863, Vanderbilt took control of the Harlem in a famous stock market corner, and was elected its president. He later sold his last ships in order to concentrate on the railroads.

His son, Cornelius Vanderbilt II (Nov 11, 1843 to Sept 12, 1899) inherited much of his father’s estate and built the famous Breakers Mansion in Newport, Rhode Island as a summer home.

Vanderbilt was the head of the syndicate that built Reliance for the 1903 America’s Cup as the defender. She was the largest yacht ever built for the America’s Cup to face the challenger Shamrock III, owned by Sir Thomas Lipton.

This was Lipton’s third challenge for the America’s Cup. The Reliance was designed and built by Nathanael Herreshoff in Bristol, R.I. Her manager was C. Oliver Iselin, and the syndicate members were Cornelius Vanderbilt III, William Rockefeller and Elbert H. Gary, founder of U.S. Steel. Reliance was the largest gaff-rigged cutter ever built, and was designed to take full advantage of the Seawanhaka “90-foot” rating rule. To save weight, she was completely unfinished below deck with exposed frames. She was the first racing boat to be fitted with winches below decks in an era when her competitors relied on sheer manpower. Despite this, she carried a crew of 64 for racing due to her large sail plan. From the tip of her bowsprit to the end of her 108-foot boom, Reliance measured 201-feet, and the tip of her mast was 199-feet tall. Her spinnaker pole was 84-feet long, with a sail area of 16,160 square-feet.

Reliance was built for one purpose, to successfully defend the America’s Cup.

“Call the boat a freak, anything you like, but we cannot handicap ourselves, even if our boat is only fit for the junk heap the day after the race,” said Cornelius Vanderbilt. Reliance’s successful career was short-lived, and she was sold for scrap in 1913.

“They tell me I have a beautiful boat. I don’t want a beautiful boat. What I want is a boat to lift the Cup, a Reliance,” Sir Thomas Lipton was quoted as saying. “Give me a homely boat, the homeliest boat that was ever designed, if she is as fast as Reliance.”

His son, Brigadier General Cornelius “Neily” Vanderbilt III (Sept 5, 1873 to March 1, 1942) was an American military officer, inventor, engineer and yachtsman.

Against his father’s wishes, in August 1896 he married Grace Graham Wilson who then disinherited him, though his brother, Alfred, ponied up a few bucks upon their father’s death to the tune of $6 million. As with other members of the Vanderbilt family, yachting was one of his favorite pastimes, and he was a member of the nine-member syndicate that built the yacht, Reliance. He was commodore of the New York Yacht Club from 1906 to 1908. In 1910, he skippered his 65-foot sloop, Aurora, to victory in the New York Yacht Club’s race for the King Edward VII Cup in Newport, RI.

This leads us to Harold Stirling Mike Vanderbilt (July 6, 1884 to July 4, 1970). He was an American railroad executive, champion America’s Cup yachtsman and champion player of contract bridge. My mom would be jealous!

Mike nearly lost his yacht, the Vagrant, on Britain’s entry into the First World War. The British competitor for the 1914 America’s Cup, Shamrock IV, was crossing the Atlantic with the steam yacht, Erin, destined for Bermuda when Britain declared war on Germany on Aug 5, 1914. The British crews received word of the declaration of war by radio.

As the commodore of the New York Yacht Club, Vanderbilt sent the Vagrant from Rhode Island to Bermuda to meet the Shamrock IV and Erin to escort them to the US. Meanwhile, among the first things done in Bermuda on the declaration, was to remove all maritime navigational aids. The Vagrant arrived on the 8th. Having no radio, the crew was unaware of the declaration of war. When they found all the buoys and other navigational markers missing, they attempted to pick their own way in through the Narrows, the channel that threads through the barrier reef. This took them directly to the fore of St. David’s Battery, where the gunners were on a war footing and opened fire. This was just a warning shot, which had the desired effect. The Shamrock IV and Erin arrived the next day. The America’s Cup was cancelled for that year.

He won six King’s Cups and five Astor Cups at regattas between 1922 and 1938. He served as commodore of the New York Yacht Club from 1922 to 1924, and achieved the pinnacle of yacht racing in 1930 by defending the America’s Cup in the J-class yacht Enterprise.

In 1934, he faced Endeavour, owned by the aviation pioneer and industrialist Thomas Sopwith. Endeavour won the first two races but Vanderbilt’s Rainbow then won four races in a row and successfully defended the Cup. In 1937, he won again in Ranger, the last of the J-class yachts to defend the Cup. He was elected to the America’s Cup Hall of Fame in 1993.

He won the North American Bridge Championships twice and Vanderbilt twice, the first in 1932 and the last in 1940. He was a runner-up at the North American Bridge Championships, and during the Vanderbilt in 1937.

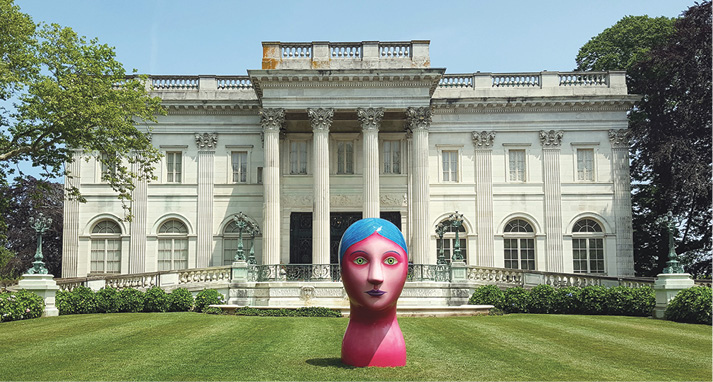

His boyhood home was the Marble House, which was built by his parents in Newport, Rhode Island. Designed as a summer cottage for Alva and William Kissam Vanderbilt by the society architect Richard Morris Hunt. It was unparalleled in opulence for an American house when it was completed in 1892. Its temple-front portico resembles that of the White House. The mansion cost $11 million, equivalent to $313 million in 2019.

His mom closed the mansion permanently in 1919 when she relocated to France to be closer to her daughter, Consuelo Balsan. There, she divided her time between a Paris townhouse, a villa on the Riviera and the Château d’Augerville, which she restored.

This leads us to a niece, Gloria Laura Vanderbilt (Feb 20, 1924 to June 17, 2019) who was an American artist, author, actress, fashion designer, heiress and socialite. She was a member of the Vanderbilt family of New York, and the mother of CNN television anchor Anderson Cooper.

During the 1930s, she was the subject of a high-profile child custody trial, in which her mother, Gloria Morgan Vanderbilt, and her paternal aunt, Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney, each sought custody and control over her trust fund.

Called the “trial of the century” by the press, the court proceedings were the subject of wide and sensational press coverage due to the wealth and prominence of the involved parties, and the scandalous evidence presented to support Whitney’s claim that Gloria Morgan Vanderbilt was an unfit parent.

In the 1970s, Vanderbilt launched a line of fashions, perfumes and household goods bearing her name. She was particularly noted as an early developer of designer blue jeans.

Sir Thomas Lipton

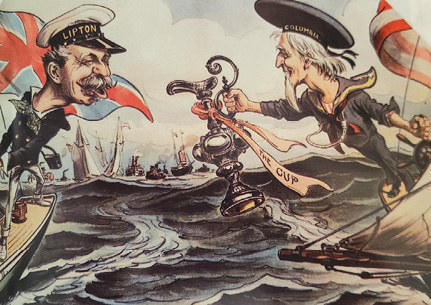

Sir Thomas Johnstone Lipton (May 10, 1848 to Oct 2, 1931) was a Scotsman of Irish parentage, who was a self-made man, merchant and yachtsman. He engaged in extensive advertising for his chain of grocery stores and his brand of Lipton teas. He boasted that his secret for success was selling the best goods at the cheapest prices, harnessing the power of advertising and always being optimistic. He was the most persistent challenger in the history of the America’s Cup.

King Edward VII and King George V both shared their interest in yachting with Lipton, and enjoyed his company. Between 1899 and 1930, he challenged the American holders of the America’s Cup through the Royal Ulster Yacht Club five times with his yachts called Shamrock through Shamrock V.

His well-publicized efforts to win the cup, which earned him a specially designed cup for the best of all losers, made his tea famous in the United States. Lipton, a self-made man, was no natural member of the British upper class, and the Royal Yacht Squadron only admitted him shortly before his death. Lipton was inducted into the America’s Cup Hall of Fame in 1993.

He was sometimes described in the press as the world’s most eligible bachelor, and carefully cultivated a public image as a ladies’ man.

The first Shamrock was a racing yacht built in 1898, and was the unsuccessful Irish challenger for the 1899 America’s Cup against the United States defender, Columbia. It was designed by third-generation Scottish boat builder, William Fife III, and built in 1898 by J. Thorneycroft & Co., at Church Wharf, Chiswick. However, her draft was too great for construction at Chiswick, and she was built at Millwall.

It was christened by Lady Russell of Killowen, and featured a composite build with a manganese-bronze bottom, aluminum topside clinker built over a steel frame, a pine decking and was skippered by Captain Archibald Hogarth.

During her trials, she raced against the 1895 America’s Cup challenger, Valkyrie III, as well as beating the Prince of Wales yacht Britannia twice in regattas on the Solent. She sailed to New York for the America’s Cup race in the summer of 1899.

The Cup defender, Columbia, beat Shamrock in all three races. She returned to Britain in the autumn of 1899, towed by Lipton’s steam yacht, Erin. She was subsequently refitted to serve as a trial horse for Shamrock II and Shamrock III.

Shamrock IV was a yacht owned by Sir Thomas Lipton, and designed by Charles Ernest Nicholson. She was the unsuccessful challenger in the 1920 America’s Cup. While the boat was launched in 1914, and soon towed across the Atlantic by Lipton’s boat Erin, she was soon dry docked due to World War I. Shamrock IV was a butt-ugly boat, almost abhorrent as the new AC75 INEOS UK! It was known as the ugly duckling, due to its scow-like bow. The boat was considerably faster than the Defender, and owed seven minutes under the newly instated Universal rule.

While Shamrock IV lost the America’s Cup, it was a public sensation. Lipton allowed tours after the last race, and reportedly 35,000 people walked aboard during a three-day period.

Shamrock V was the first British yacht to be built to the new J-Class rule. She was commissioned by Sir Thomas Lipton for his fifth America’s Cup challenge. Although refitted several times, Shamrock V is the only original J-class never to have fallen into dereliction.

The services of Charles Ernest Nicholson were once again employed to design the challenger, and she was constructed at the Camper and Nicholson’s yard in Gosport. Shamrock V was built from wood, with mahogany planking over steel frames and most significantly, a hollow spruce mast. As a result of rule changes, she was the first British contender for the America’s Cup to carry the Bermuda rig.

Following her launch on April 14, 1930, she showed early promise on the British Regatta circuit, winning 15 of 22 races. She also underwent continuous upgrading with changes to her hull shape, rudder and modifications to the rig, to create a more effective racing sail plan before departing to America.

Four New York syndicates responded to Lipton’s challenge, each creating a J-Class, Weetamoe, Yankee, Whirlwind and Enterprise. This was a remarkable response, particularly during the time when the depression hit America, with each yacht costing at least half a million dollars. This served to highlight that despite the J-Class’s immense power and beauty, their Achilles heel would be the exorbitant cost to construct and race them. Winthrop Aldrick’s syndicate, Enterprise, emerged from the competitive round robins as the eventual defender.

Enterprise was the smallest J-Class to be built. Her size being an early indication of the ruthless efficiency that was employed by the renowned naval architect Starling Burgess. The efficiency of design was coupled to a number of pioneering features, such as the Park Avenue Boom, hidden lightweight winches and the world’s first duralumin mast.

The first of the best of seven races was a convincing victory for Enterprise, who won by nearly three minutes. Shamrock V was to fare worse in the second race, losing by nearly 10 minutes. The third race finally provided the assembled thousands on the shore at Newport, the racing they craved. Shamrock V’s initial lead at the start was relinquished to Enterprise after a tacking duel.

Following this surrender, disaster struck as Shamrock V’s main halyard parted, and her sail collapsed to the deck. The fourth race clinched the cup for Enterprise, after which Sir Thomas Lipton was heard to utter “I can’t win.”

Shamrock V’s challenge was plagued by bad luck, and haunted by one of the most ruthless skippers in America’s Cup history, Harold Vanderbilt. Sir Thomas Lipton, after endearing himself to the American public for 31 years and five attempts, died the following year, never fulfilling his ambition to win the Cup.

Again, much thanks to my invaluable set of World Book’s for much of my background, along with a bit of Wikipedia, the libraries at Columbia and the General Theological Seminary in New York where much of my research was completed.

If this history interests you, drop a note at mark@yacht manmagazine.com