Lessons Learned – by Pat Carson

There Is Always Time For Safety

I have been asked many times if it is necessary to do an engine room check every time we plan to get a boat underway. My answer is always an unequivocal yes, every time. I never start up a boat until I have checked the fluid levels, looked around the engine room and have satisfied myself that nothing unusual has been going on down there since the last time I operated it, even if that was just yesterday.

Engine room checks after fueling are especially important. See the March 2014 issue of the Yachtsman Magazine for my article on Fueling Safety and the reason we always inspect the enclosed spaces after taking on fuel. On some vessels, access to the engine room is easy and the space is large enough to move around, but on others the access is difficult and the space is cramped. The more difficult the access – having to move furniture to get to that hatch in the saloon sole for example – the less often we tend to go down there and look around. However, remember there is an abundance of equipment in that machinery space whose failure can cause problems. With regular visual checks we can help to avoid those problems.

Fueling a boat is not like fueling a car. Checking the engine room for spills or odor is especially important after taking on fuel. With our cars we pull up to the pump, put the nozzle in and pull the trigger, then walk away to make phone calls or just get out of the weather. The pump clicks off when we are done, sometimes we squeeze the trigger a few more times for good measure and we just put the nozzle away and leave. Easy and relatively safe. Unfortunately, the same procedure on a boat is simply not safe. Several marinas have well placed signage to assist with the proper fueling procedures, but these can go unnoticed when we are in a hurry.

For proper and safe fueling we:

- 1. Shut off all engines. This includes the generator.

- 2. Shut down all electrical systems.

Both the AC and the DC electrical systems should be shut down. I find the easiest way to do this is to turn off the DC power main battery disconnects, Perko switches for example and the main breaker for AC. Be sure to shut down the breaker for the inverter if your vessel has one. Doing this prevents the possibility of an electrical spark igniting fuel vapors. - 3. Before you start adding more fuel, know how much is currently in the tanks and have an idea of how much room there is for more.

If your boat holds 200 gallons and the gauge shows half-full, then you can expect to add less than 100 gallons to bring the level near 100%. If you add more than expected understand why. Was the fuel level gauge inaccurate? Did fuel actually go into the tank I intended? Is the tank the capacity that I think it is? - 4. Extinguish all open flames.

This includes not only the obvious smoking material but also any gas heaters or barbeques that you have recently used and still may be hot. - 5. Close all portholes, hatches and doors and have all passengers disembark.

When we add fuel to the tanks, air is vented to the atmosphere through the tank vents. These vapors are explosive and can find their way into confined spaces. - 6. Discharge any static electricity from the nozzle by making contact with the fill plate first.

The fill plates should be electrically bonded to the vessel’s ground system and will safely discharge any static electricity. During fueling, be certain to keep the nozzle in contact with the plate. It is also a good idea to know which fill is for which tank. I have fueled boats with as many as six tanks and the same number of fill pipes and vents.

Fill pipes for water and for holding tank pump outs on many boats appear the same. Do not put fuel into the wrong tank! - 7. Maintain control of the nozzle as you fill.

I have been to some fuel docks that will terminate your fueling if you do not hold onto the fill nozzle at all times. Some boat designs have the fill plates installed almost vertically and the nozzle is not secure by itself. Many of the fuel nozzles are not reliable, may not automatically shut off and fuel will spill out the vent or out the fill pipe. Listen as the tank fills, you can hear the sound change as the fuel tank fills. - 8. Don’t overfill

As fuel warms it expands. The tank vents on most boat designs are lower than the fill pipe so it is possible to spill fuel from the vents if you try to squeeze in as much fuel as possible. As a general rule, only fuel to 95% of capacity. - 9. Check the vent

As you fill the tank with fuel, air can be heard or felt exiting the vents. If it is not, then the vent may be clogged or not connected, or you are not putting fuel in the tank. I have witnessed several instances where the vent has been filled with debris and not venting, making fueling very slow. Also, know which vent is for the tank you are filling. - 10. Safety check

Once fueling is completed, and before anyone gets back on board, you should do an engine room check. Look for any liquids in the bilges and smell for the odor of fuel. A while back I fueled a boat with a client for the first time and we found several gallons of fuel in the bilge after fueling. A close inspection revealed a cracked fuel filler hose that allowed a significant leak of fuel while fueling. Fortunately, this was a diesel-powered vessel and we only had a mess to clean up.

Owners of boats with diesel engines and generators will often leave the engines running and the vessel powered. Most commercial fuel docks and boat operators do not find this practice to be a safety hazard since diesel fuel is not aromatic at room temperatures and cannot explode. It is your call; personally, I keep the diesels running but will comply with a request from a fuel dock attendant to shut them down.

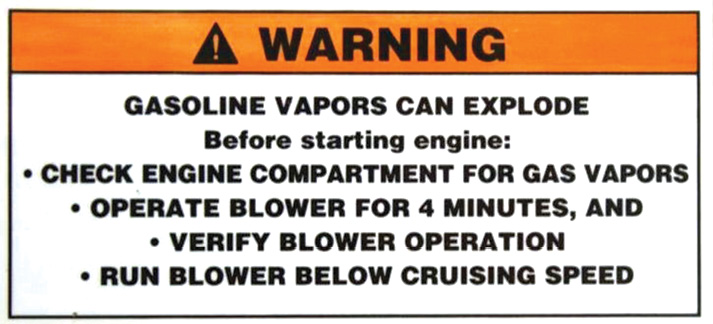

A final word about bilge or engine room blowers. I have been with clients practicing the safe fueling drill and have been asked if we should run the blower for the recommended four to five minutes. I answer that question with why do we have engine room or bilge blowers? Bilge blowers are designed to exchange air in the enclosed engine room space that potentially may contain fuel vapors. If we have done a safety check, then we know that there are no vapors below decks and the engines are safe to start. That said always remember that running the engine room blowers is not a substitute for going into the engine room or other enclosed spaces where the fuel tanks are located to look and sniff for fuel vapors. Many diesel-powered boats do not have engine room blowers due to the inherent safety of diesel fuel. In the interest of safety, I do turn on the blowers after closing up the engine room but make it a practice to give a quick sniff of the air coming out the vent. This air should not have any fuel smell to it and again confirms that there are no flammable vapors below decks.

Lessons Learned

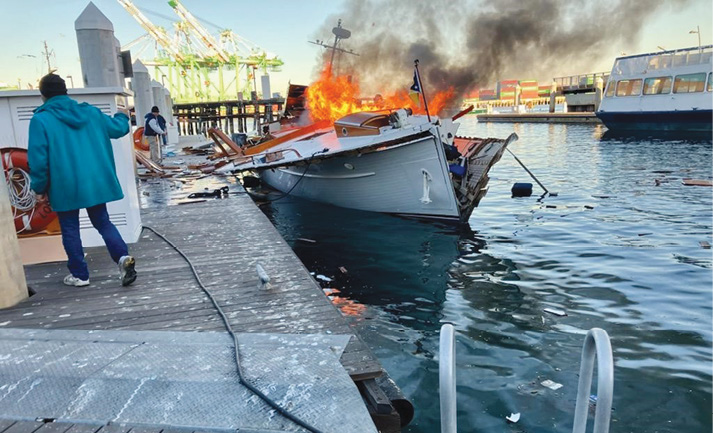

Recently a very unfortunate incident occurred at a local marina that resulted in the total loss of the vessel and the owner seriously injured. Although not all of the details and facts are yet available, what we do know is that there was an explosive concentration of gasoline vapors in the engine room, and when attempting to start the engines something created a spark and an explosion occurred. A few days prior the owner of the vessel completed a few repairs to the engines, added fuel and prepared the vessel for a cruise. Clearly something went wrong. It is very fortunate that the damage was not worse. Although the explosion resulted in the vessel sinking and the owner being injured, there was no resulting fire to other structures and the occupants of the neighbor boats were not injured or their vessels damaged.

Accidents are almost always the result of several things occurring in just the right order at just the right time. Breaking the chain at any point would prevent a catastrophic result. In this case there was an apparent fuel leak, an enclosed space accumulated flammable vapors and a device that created a spark. Eliminate any one of those and the result would be different. Gasoline can be handled safely. In 2022 nationally there were 183 vessels involved in an accident where the primary cause or primary contributing cause was Ignition of Fuel that resulted in a fire or explosion. These accidents resulted in 109 injuries and three deaths. Statistically, Ignition of Fuel does not rank in the top 10 primary causes of accidents at just 1.3% of total accidents. However, it accounts for 10.5% of total damages and 0.5% of deaths, but it is one of the more easily prevented. Interestingly, just 20.2% of fuel explosions were on enclosed motor yachts while 50.2% were on an open motorboat, and 13.1% on a pontoon style vessel. Houseboats, personal watercraft and unknown vessels make up the balance.

Follow safe fueling practices, conduct engine room checks after fueling and before starting the engines, use only USCG approved parts that are explosion proof.

I hope that if you get anything out of this article it is to never start a boat engine without completing a thorough engine room inspection first and to not sacrifice safety in the interest of expediency. As we live by on the commercial boats, “there is always time for safety!”

A Final Word

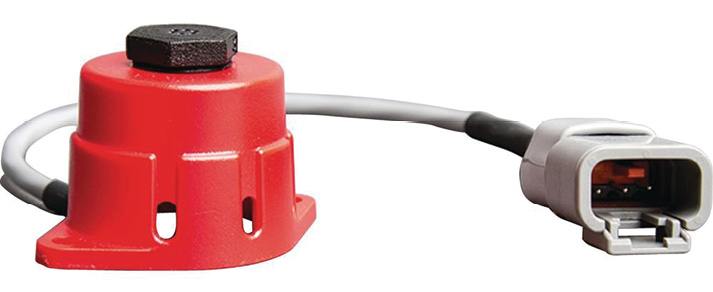

Many new gasoline powered vessels come with fume detectors as standard equipment. These devices will detect gasoline vapors and sound an alarm or in some installations prevent the engine from cranking over and starting. There are several of these detectors available for retrofit to vessels that do not have them already installed.

The devices are quite simple, consisting of a sensor that is placed in the bilge and a display placed at the helm. There are some that have automatic blower controls, engine lockouts, multiple sensors and are able to detect a variety of gasses. Adding a basic system to most any gasoline powered vessel is easy and should take only a few hours to install. The added safety is worth the effort.

Now that we have gone to the trouble of installing a fume detector, do not cut corners by using nonmarine approved devices and hoses. Marine equipment is designed to be explosion proof and will not generate a spark during normal operation where nonmarine devices may. Marine parts may cost more, but there is a reason.

Until next month I am going to sit back, enjoy a fine port that was a gift from a client and a cigar as I watch my new gasoline vapor detector keep an eye on my bilge. Until next month, please keep those letters coming. If you have a good story to tell, I love a good story. If you have good photos of right and wrong, please send them and I will include them in next edition of “is it right or is it wrong.” I can be reached at patcarson@yachtsmanmagazine.com