Lessons Learned – by Pat Carson

That Was Predictable

Abandoned and derelict vessels are a problem for not only the waters in our backyard but many United States harbors, bays and shorelines. Sunken, stranded, abandoned and derelict vessels are an eyesore, can become hazards to navigation and these vessels can disperse oil and chemicals that remain on board posing significant threats to natural resources as well as physically destroying sensitive marine environments and life.

For years, people living in the Delta area have been blessed with views of derelict ships peaking over the horizon at the end of Eight Mile Road in Little Potato Slough. Amid the cluster of eyesores, there are a total of four ships. Two sit above water and two have sunk. The Aurora, a 293-foot former ocean liner, the Chaleur, a 140-foot former Canadian Minesweeper, the former USCG Cutter Fir and the tugboat Mazapeta.

All of them are in the mud and not going anywhere under their own power, but the Fir and Aurora have not sunk, yet. The Minesweeper Chaleur sunk several years back and initially leaked hazardous waste into the Delta. The USCG stabilized the leaks when it sank and removed as much fuel as they could before sealing up the holes. The Mazapeta sunk on Sept. 4, 2023, with approximately 1,600 gallons of diesel and engine oil on board. During the dewatering operations approximately 593 gallons of petroleum product and 26,000 gallons of oily water mixture have been recovered from inside the containment boom. Is this a happy ending to just another derelict vessel problem?

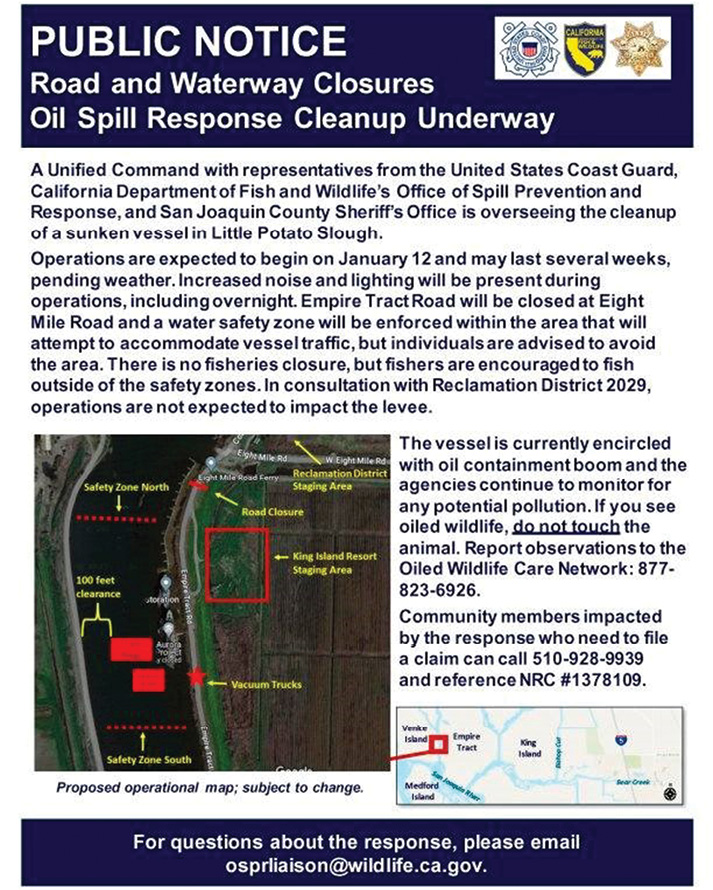

In mid-January 2024 a unified command consisting of the United States Coast Guard, California Department of Fish and Wildlife Office of Spill Prevention and Response and the San Joaquin County Sheriff hired Parker Diving and Salvage to begin the process of removing the 1940’s era tugboat Mazapeta. After a week of dewatering, defueling and removing hazardous waste items such as batteries, Parker Diving and Salvage raised the Mazapeta using a crane barge and dewatering pumps. Now the City of Stockton has taken control of the wreck and plans to move the vessel to Mare Island for final disposal.

The Recreational Boat Problem

With roughly 626,642 registered recreational vessels in 2022, California has the fifth largest boating population in the United States behind Florida (1,004,240), Minnesota (822,450), Michigan (809,750) and Ohio (652,858). Every year many of these vessels are no longer wanted by their owners and they either sell, donate, scrap or abandon them. While responsible owners dispose of vessels lawfully, other owners abandon them on state waterways where they become a hazard to navigation and interfere with boating traffic. As these vessels deteriorate, they leach toxic chemicals and fuel into our water. On any given day of boating in San Francisco Bay or the Delta it is common to see at least one partially sunk boat someone tried to scuttle. Rather than pay for disposal, some boat owners opt for the easy and illegal way out when the vessel has outlived its usefulness. They abandon them in our waters where they pose, did I already say, a serious hazard to navigation and to the environment!

You Have Options

Do you have a boat you no longer want and would like to get off your hands? There are several options available versus scuttling her in the Delta. One option is to contact a used boat parts dealer that may accept your old vessel for its parts, which they then resell. Some dealers may purchase the vessel from you for the value of the useable parts minus the total cost of dismantling the vessel and recycling or disposing of hazardous waste. Check around, each dealer has their own specific requirements for the length and type of vessel they will accept, and the value the parts are to them. A second option to abandoning an unwanted trailerable vessel is to take it to a landfill site for disposal. Many local transfer stations and landfill agencies will accept them for disposal. A quick call for details regarding acceptance, costs and hazardous waste restrictions is all it takes and soon that eyesore may just be out of your driveway.

The third option to abandoning a vessel is to turn it in to a state facility that receives grant monies from the Abandoned Watercraft Abatement Fund, AWAF. Legislation in 1997 created the AWAF and made the primary source of funding from the Harbors and Watercraft Revolving Fund or HWRF, boater fuel taxes and registration fees and fines levied and collected from owners of abandoned vessels. Current law makes abandoning a vessel punishable by a fine of not less than $1,000 or more than $3,000 and 80% of those fines are deposited into the AWAF. The AWAF is a reimbursement grant that funds abatement, removal, storage and disposal costs of abandoned, wrecked or dismantled vessels. In 2010, legislation created another government program called the Vessel Turn-In Program, VTIP, which is also a grant but was designed to be proactive in preventing owners from abandoning unwanted vessels. VTIP is zero cost to boat owners and is as easy as contacting your local agency to make arrangements for dropping off the vessel. In Jan. 2016, legislators combined the AWAF and VTIP into the Surrendered and Abandoned Vessel Exchange, SAVE. The SAVE program combines both programs into one, making it easier for public agencies to apply and manage one grant and use the funds for both the AWAF and VTIP as needed. Private businesses cannot apply for a SAVE grant; however, they may work through a local public agency that is participating in the SAVE to remove abandoned vessels on their private property, surrender vessels in which they hold title through the VTIP and remove hazardous marine debris.

Since the start of the AWAF in 1999, some 2,000 recreational vessels have been removed from our waters and another 350 removed under the VTIP since it was enacted in 2010. The average cost of removing a vessel under the AWAF is $3,300 and under the VTIP it is only $1,400. Seems like a couple of successful government programs. In both 2022 and 2023 the SAVE program awarded $2.75 million in grants with a paltry sum of $150,000 awarded to the San Joaquin County Sheriff each year. Contra Costa County was awarded over $600,000 combined in 2022 and 2023.

The Harbors and Watercraft Revolving Fund supports boating related activities. The HWRF is used to support various boating related activities, including management of invasive aquatic plants and other species, as well as local assistance grants for boating facilities and safety programs. The department also makes regular transfers from the HWRF to the Public Beach Restoration Fund, which provides grants for sand replenishment projects. The HWRF receives a significant portion of its revenue from vessel registration and renewal fees. Annual expenditures from the HWRF have nearly doubled in less than a decade – increasing from $48 million in 2014-15 to $94 million in 2020-21 – due to factors such as increases in employee compensation, addressing a growing prevalence of aquatic invasive species and because of new activities that have been shifted onto the fund.

More Government Agencies

These are not the only government agencies trying to clean up our waterways. Up until 2011 the State Lands Commission would remove any abandoned vessel trespassing on state property. However, between removal fees and court actions, the process became expensive. A prime example is the approximate $200,000 cost of removing the “old” Spirit of Sacramento, a 100-foot paddlewheel boat from the Sacramento River.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Agency, NOAA, maintains a large database of shipwrecks, dump sites, navigational obstructions, underwater archaeological sites and other underwater cultural resources. The Resources and Undersea Threats database includes approximately 20,000 shipwrecks in the territorial waters of the United States. In 2010, NOAA was tasked with identifying those potentially polluting shipwrecks in United States waters that would cause the greatest ecological and economic impacts. This project supports the United States Coast Guard and the Regional Response Teams, as well as NOAA in prioritizing threats to coastal resources. In late 2015, NOAA launched an abandoned and derelict vessel InfoHub as the go to source for information regarding funding, policy and removal efforts. Since the inception, more than $1.1 million has been awarded to organizations and state agencies to fund marine debris removal programs including abandoned and derelict vessels.

The Federal Oil Spill Liability Trust Fund, OSLTF, financed through taxes on oil, paid for the removal of the “new” Spirit of Sacramento when, in Sept. 2016, she sank in False River reportedly due to mechanical failure. This vessel had been purchased at an auction from the County of San Mateo for $1,000, and shortly after left Oyster Point Marina under her own power for the Delta. Unfortunately, in the middle of the night she rolled over and sank. The crew of two managed to escape in a dinghy and have not been seen again. When the owner of the vessel refused a federal order to remove both the fuel and the vessel, the United States Army Corps of Engineers and the United States Coast Guard stepped in and just a few weeks later the vessel was re-floated, drained of water and put under tow to the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers docks in Sausalito to remove the 600 or so gallons of diesel fuel still on board. Total cost was estimated to exceed $250,000.

The OSLTF act establishes liability for damages and the costs resulting from the oil spills. The act requires the party responsible for the vessel or facility to reimburse injured parties for the removal cost and damages resulting from a spill. The USCG has a $25 million annual budget for administering this fund.

The California Harbors and Navigation Code 525 makes it a crime to abandon a vessel in a public waterway or on public or private property without permission of the property owner. A boat is considered abandoned if it is left in a disabled state for more than thirty days. The fines for abandoning a vessel range from $1,000 to $3,000 plus the costs of the removal. If the boat is not a total loss, the local government agency can sell or destroy it and hold the owner responsible for the costs of the sale or destruction.

Recently legislation has been introduced that would open up the AWAF for removal of commercial vessels. Currently only noncommercial abandoned vessels qualify for AWAF grants, and because local jurisdictions typically lack funds for vessel abatement, many commercial vessels are not promptly removed. However, opening the AWAF funds for commercial vessel removal could quickly wipe out an already underfunded program. Even with the $1.75 million AWAF earmark, the annual grant applications exceed $2.2 million. In addition, commercial vessels do not pay fuel taxes, registration fees or have fines levied against them which are the source for AWAF funding. The removal of commercial vessels should be the responsibility of the business entity that owns the vessel not the recreational boat owners. Under federal law all vessel owners are responsible for cleanup costs and damages for any pollutants spilled from their vessel. Most pleasure craft yacht insurance policies include coverage for marine pollution liability, usually up to the policy limit. I wonder how many of those abandoned vessels leaked oil, gas, coolant, battery acid and other contaminants and had insurance coverage to cover the cost of cleanup?

Lessons Learned (Are There Any?)

None of those boats in Little Potato Slough belong there. Herman & Helen’s is gone and will probably never return. The docks and mooring structures either have completely fallen into the water or are well on their way, and it would cost millions of dollars to resurrect the resort. With no marina there is no entity from which to lease a space. All the boats at the end of Eight Mile Road are squatting, paying no rent and have no electricity or sanitation.

The Minesweeper Chaleur was the first to go and let loose debris and hazardous fluids. Now the Mazapeta is on the bottom with some 1,600 gallons of diesel spilling into the Delta. The Fir will probably be next as the owner passed away last year and apparently no one has any interest in carrying the “restoration” project forward. The vessel will likely rot away sitting in the mud of Little Potato Slough. Not to worry about spilling any fuel oil however, as I understand that the thousands of gallons of fuel the owner boarded a short time before his passing have “mysteriously” disappeared.

Who is paying for the cleanup of the Mazapeta and the Chaleur? Well, ultimately you will. For now, the City of Stockton has approved a $450,000 fund to tow the vessel to Mare Island. That is your tax dollars if you live in Stockton. But the question is why is the City of Stockton paying for the cleanup? Well, it seems that the Stockton MUD drinking water pump station located just a few hundred yards from the derelict vessels has seen a catastrophic increase in filtration costs resulting in the shutting down of that pump station. The $450,000 is a paltry sum when compared to their increased filtration costs and lack of use of the facility.

Do you think this will be the last of the derelict vessel problems? I do not think it will be. With the Fir and the Aurora sitting there they will certainly draw more derelicts to join them. Even with pretty exterior paint jobs, work that should have been done at a boat yard where they are equipped, regulated and inspected to contain contaminants, these boats are like a neon sign attracting more unwanted eyesores. Remember the Aurora and the Mazapeta were thrown out of San Francisco and told never to come back. As the Bay Area counties get more aggressive in forcing the junk out of their jurisdictions, it is inevitable that the majority will find a welcoming home in a back slough of the Delta.

Do not get me wrong, I appreciate a classic ship that has been restored or is being restored more than the next guy. But I also understand what it takes to restore, operate and maintain a historical ship. Having been involved with the USS Potomac for more than a decade I have seen what it takes, and it is not easy.

The USS Potomac Association is a well-run organization with a well-connected board of directors, a dedicated staff, volunteers donating over 8,000 hours every year and 60+ income generating charters every year they still have operating budget struggles. When resurrected and made operational, the association had hundreds of thousands of donated hours by union craftsman to bring the USS Potomac back from the rusted hulk tied up at Treasure Island staying afloat only with large pumps. The boats in Little Potato Slough have none of these assets, and without them they are doomed to failure. I personally do not want any of my tax dollars, whether from the HWF, the USCG, the Army Corps of Engineers, the DBW, county or city funds donated to a lost cause. The Delta counties need to pass ordinances now that will prevent more junk boats from coming our way and go after the responsible parties for the current problems while they can.

Saving a classic yacht or ship is a noble effort. But if you are not well funded and have deep pockets someone else will end up paying and that someone else is the taxpayer. The estimated cost of removing the Mazapeta is $4 million, and they plan to leave the sunken Chaleur rotting away in the mud. By the time you read this (mid-February) the Mazapeta should be at the Mare Island scrappers and hopefully the Chaleur is right behind her. Next up for disposal are the Fir and the Aurora, and let’s stop anything more from arriving to squat on public lands. Write your county officials and push for strong ordinances to clean up the current mess and prevent future problems.

Time for me to sit back, enjoy a good glass of port, light up a fine cigar and try to nurse the headache that I got from reading government documents. There are so many departments and agencies, all with hard to remember acronyms managing our money that it is surprising any of it trickles down to get actual vessel removals accomplished. Until next month please keep those letters coming. If you have a photo or two, please share. If you have a good story to tell, send an email to patcarson@yachtsmanmagazine.com as I love a good story.