Lessons Learned – by Pat Carson

Conception Fire Update

On Monday, Sept 2, 2019 at approximately 0314 Pacific Daylight Time, U.S. Coast Guard Sector Los Angeles/Long Beach received a distress call from diving vessel, Conception, which had 33 passengers and six crew on board. “Mayday, Mayday, Mayday. Conception, Platts Harbor, north side Santa Cruz, 39 POB. I can’t breathe. 39 POB. Platts.” Those were the last words, at 3:14 a.m., that the captain made in a distress call over the VHF radio to the U.S. Coast Guard on the morning when the Conception dive boat caught fire and sank last September, with 39 people on board.

At the time the fire started, five crewmembers were asleep in their bunks in the wheelhouse and crew staterooms on the upper deck, and one crewmember and all 33 passengers were asleep in the bunkroom. A crewmember sleeping in an upper deck stateroom was awakened by a noise and got up to investigate. He saw a fire at the aft end of the sun deck, rising from the saloon compartment below. The crewmember alerted the four other crewmembers sleeping on that deck. As crewmembers awoke, the captain radioed a quick distress message to the Coast Guard before evacuating the smoke-filled wheelhouse.

Approximately 78 minutes after the initial distress call at 0432 the Coast Guard and other first responder boats arrived on scene to extinguish the fire and search for survivors. Helicopters also aided in search efforts. The vessel burned to the waterline, and just after daybreak the Conception sank in about 60-feet of water. Thirty-three passengers and one crewmember died.

Investigators

The accident was severe enough to merit three separate lines of inquiry: a federal criminal investigation led by the Coast Guard Investigative Service, an NTSB safety investigation and a U.S. Coast Guard Marine Board of Investigation (MBI), a formal process reserved for the most serious casualties. The NTSB is the first to offer published conclusions.

The National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) has authority to investigate and establish the probable cause of any major marine casualty or any marine casualty involving both public and nonpublic vessels under CFR49 section 1131. The NTSB does not assign fault or blame for a marine casualty; rather as specified by NTSB regulation, investigations are fact-finding proceedings with no formal issues and no adverse parties and are not conducted for the purpose of determining the rights or liabilities of any person. Reading CFR49 Section 831.4. Assignment of fault or legal liability is not relevant to the NTSB’s statutory mission to improve transportation safety by conducting investigations and issuing safety recommendations. In addition, statutory language prohibits the admission into evidence or use of any part of an NTSB report related to an accident in a civil action for damages resulting from a matter mentioned in the report.

The United States Coast Guard, USCG Marine investigators carry out investigations of commercial vessel casualties and reports of violations per CFR46 chapters 61, 63, and 77. The primary purpose of the USCG investigation is to ascertain the cause or causes of the accident, causality or personal behaviors or if any violation of federal law has occurred and to determine if remedial measures should be taken. The USCG is authorized to enforce incidents involving vessel personnel, boating accidents, waterfront facility causalities, deep water port causalities, marine pollution incidents, accidents involving Aids to Navigation and accidents involving structures on the Outer Continental Shelf. The results of their investigations play a major role in changing current law, developing new law and regulations and implementing new technologies. During the course of the USCG Marine Board of Investigation (MBI) the panel must decide the factors that contributed to the accident, whether there is evidence that any act of misconduct, inattention to duty, negligence or any willful violation of law on the part of any involved person contributed to the causality. In some instances, the MBI will identify pressing safety issues and will issue safety alerts that are available to the public through the Coast Guard Office of Investigations and Causality Analysis website.

In parallel, criminal investigations by the Coast Guard Investigative Service (CGIS), Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (ATF) and the Department of Justice (DOJ) are working in coordination with the U.S. Attorney’s office.

NTSB Findings

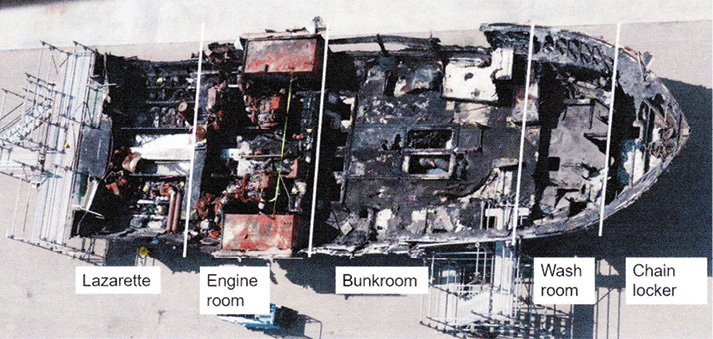

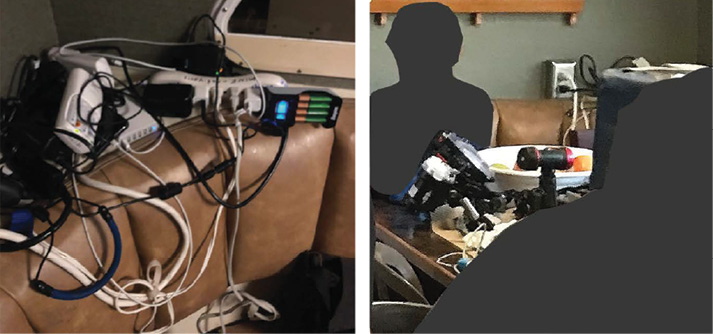

The descriptions of the fire from the interviews of the crew indicate that the fire did not begin in the chain locker, engine room, lazarette, galley or upper deck. The crew descriptions consistently identify the aft portion of the saloon compartment on the starboard side as exhibiting more intense fire involvement at the time of discovery. No physical evidence was recovered that could be identified as an ignition source or indicate a specific ignition location within that area. Therefore, the cause of the fire is undetermined. Based on the crew interviews and statements from previous passengers, it is believed that there were numerous electronic devices being charged overnight in the aft portion of the saloon. Batteries, and in particular, Li-ion batteries, have a known and documented history of initiating accidental fires. In the past, the Consumer Product Safety Commission has issued numerous product safety recalls due to fires caused by electronic devices with defective batteries and chargers. The NTSB has investigated accidents in which battery failures have led to fires. The Federal Aviation Administration has strict regulations on the carriage of Li-ion batteries aboard passenger aircraft based on a long history of incidents involving fires. It is therefore reasonable to include lithium-ion battery failure as a possible ignition source in this fire scenario. Another potential source of ignition is the vessel’s electrical system in the saloon compartment. An energized electrical system has the potential to become a source of ignition when elements of the system age, are improperly installed or are accidentally damaged. Crew interviews revealed that sometimes electrical work such as the replacement of lighting electrical fixtures in the saloon was done by crew members who were not licensed electricians. Although examination of the Conception’s electrical system was not possible, the examination of the Vision and the similarity of the two vessels would suggest similar electrical installations and conditions. Additionally, although the Vision was not in service at that time on Oct. 2, 2019 a Coast Guard inspection found 19 electrical system deficiencies throughout the vessel. Some of the deficiencies cited were a result of work being done at the time. Deficiencies in the saloon and galley area included corrosion, improper connectors and signs of overload on power strips. Deficiencies of this type can lead to electrical system failure conditions capable of initiating a fire. It is reasonable to include the vessel’s saloon electrical distribution system as a possible ignition source in this fire scenario. Besides the electrical system in the saloon and the charging of electronic devices and batteries, there doesn’t appear to be other sources of ignition energy available to initiate a fire in the aft interior portion of the Conception’s saloon. On the exterior of the aft portion of the saloon compartment in the vicinity of the stairway to the upper deck there was a large polyethylene trashcan. Undetermined ignition sources in this area such as improperly discarded smoking materials cannot be discounted. Therefore, the potential ignition sources in the vicinity of the aft portion of the saloon that are the likely sources of the fire are:

- Failure of batteries being charged in chargers or in devices

- The vessel’s saloon electrical system

- Undetermined ignition sources such as improperly discarded smoking materials

Li-ion Battery History

At this time, the USCG does not have any guidance on the suppression of lithium-ion battery fires so we can look to other sources that have to deal with this new hazard. The Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) has issued a written advisory on dealing with in flight battery fires. Apparently, any given flight may contain hundreds of LI-ion cells in phones and laptops and that many rechargeable devices involved in these fires such as wireless headphones and especially e-cigarettes which were not even on the market a few years ago. On average the FAA reports that there is one Li-ion battery fire on board an aircraft every 11 days. Battery fires are particularly dangerous because they burn very hot, can emit toxic by-products and tend to flare up even after it seems like they have been extinguished. The FAA guidance indicates that the best way to cool a runaway battery is, believe it or not, with plain old water. After extinguishing the fire, douse the device with water or other nonalcoholic liquids to cool it and prevent additional battery cells from reaching thermal runaway. So, what kind of fire extinguisher should you use in this scenario? Li-ion batteries are considered a Class B fire, so a standard ABC or BC dry chemical fire extinguisher should be used. Li-ion batteries contain liquid electrolytes that provide a conductive pathway, so the batteries receive a B fire classification.

As included in the NTSB report, a small fire involving the charging of a Li-ion battery took place on board the Conception’s sister ship, the Vision, about a year before the fire aboard the Conception. On Oct. 8, 2018 between 0415 and 0430 in the morning, a passenger who was awake in the galley heard a “hissing” noise and then a loud “bang” which came from the bookshelf located at the aft starboard side of the saloon (the Conception did not have a bookshelf in the same area.) Another passenger, who was returning to the bunkroom after using the head on the aft deck also heard the noise, which drew his attention to a fire on the bookshelf. He stated that the fire looked like a “torch” flame, and a battery charger which was charging two Li-ion batteries was emitting smoke. The passenger in the galley grabbed a dry chemical extinguisher from the galley, and both passengers went to the battery charger. The passenger without the fire extinguisher unplugged the charger, grabbed the unburnt end of the charger, brought it out to the main deck and threw it in to the rinse bin located under the stairs to the sun deck. The passenger with the fire extinguisher stated that he discharged one “shot” on the bookshelf after the battery charger had been removed to extinguish the smoldering paper books on the shelf. He then grabbed a sponge and wetted the bookshelf and items on it to prevent reignition. Afterward, the passenger went to the wheelhouse and informed the captain who in turn examined the batteries and charger in the rinse bin. The batteries and charger were removed from the rinse bin and thrown overboard. One of the passengers interviewed stated that there was soot residue and scorch marks on the books and the shelf. According to the captain on the Vision at the time, who was filling in as a relief captain, he photographed the charger and sent this to another captain in the Truth Aquatics fleet. Upon returning from the trip, he stated that he had informed the owner of Truth Aquatics, as well as the captain that took the Vision on its next trip. The owner of Truth Aquatics stated that he was only made aware of the small fire on the Vision after the accident on the Conception. The owner noted that at the end of each trip each captain was required to complete a “Trip Payment Report,” which required multiple handwritten entries related to the voyage conducted, including the number of people on board, the amount of fuel used and the number of engine running hours. At the bottom of the form there was a “special comments about the trip section” where the captain on duty was required to enter any notable incidents that occurred during the trip, including “any accident, bad weather, notable rescues or incidents.” Investigators reviewed the completed form for the Oct. 7-10 trip for the Vision and found no entries in this section. The two batteries that caught fire were for an underwater diving light, and according to the owner, the batteries had been removed from the light, were connected to a separate charger and plugged into a power strip on the bookshelf. The lithium-ion batteries were each 3.7-volts and capable of 5,000 milliamp hours. According to the owner of the flashlight, he purchased the item from Amazon.com about a year earlier. The batteries were original to the dive light and were not replacements. There was no report to the Coast Guard of this incident, nor was there any requirement to do so.

Lessons Learned

The cause of the casualty has not yet been definitively established, but an electrical fire or battery charging fire is the suspected cause. The dive boat operator offered passengers access to 120-volt power strips for the purpose of recharging high capacity batteries for camera gear, underwater scooters and other equipment. It is suspected that the load on the circuit may have exceeded the electrical system’s design limits or that one of the batteries may have overheated and caught fire. The U.S. Coast Guard has issued a preliminary warning to passenger boat operators to consider limiting battery charging and excessive use of power strips.

As recreational boaters we can learn from this maritime casualty. Have smoke detectors installed in locations where a fire is likely to start and in the sleeping quarters of your vessel. Limit the overnight unattended charging of Li-ion battery powered devices, especially in the area of the emergency pathway to safety. Have handheld fire extinguishers placed in several locations throughout your yacht. The NTSB reports also identified “potential fire safety issues,” including flammable interior materials, size and accessibility of emergency exits and the fact that both exits from the bunk room led to the same compartment. Know where your emergency escape exits are located and make certain that they are accessible. Many yachts have an overhead hatch in the forward stateroom that for some folks would be impossible to crawl through. In many designs the aft stateroom has a small port that may or may not be functional or large enough to crawl through.

Truth Aquatics was generally well regarded among regulators, current and former employees, customers, and other dive boat operators in Southern California. According to the Assistant Chief, Inspection Division, Coast Guard Sector LA/Long Beach, Truth Aquatics and the company owner “had a good reputation for being good operators. They were always more than willing to engage in conversation about vessel operations. We’ve always had a good relationship with Truth Aquatics.” A customer who had made several trips on Truth Aquatics vessels stated that the company was “considered to be the top [dive boat] outfitter,” and a former captain of the Vision described the vessels as “the safest boats on the coast… No expenses were spared.”

During my SCUBA years I was a frequent passenger on the Truth Aquatics boats and recall them to be a first-class operation. None of us can afford to take safety for granted.

Epilog

The text message from the client read, “URGENT, OUR DOCK IS ON FIRE AND OUR BOAT NEEDS TO BE MOVED IMMEDIATELY!” Not exactly the kind of text you want or expect to receive at 1915 on a usually quiet Monday summer evening, and I was in Santa Barbara on a yacht delivery. Yet there it was, and fortunately Captain Leslie was at home, jumped in the truck and put more lead in the accelerator foot than normal. It is fortunate that our home is in nearby Rio Vista, and while in route to Ox Bow Marina she placed a call to the client in hopes to obtain details. Only the barest of facts were known by the client. G dock was on fire and the cause appears to be an explosion of some nature on a nearby houseboat.

Most of our Delta readership has likely heard of the recent fire at the beautiful Ox Bow Marina. A fire on board a vessel or at a marina is never a good thing regardless of size and this was no exception.

Captain Leslie stated “I could see the orange glow as I drove up on the levee approach to the marina. The responders were holding the fire and attacking it from both the dock and from the water.” There would be no moving of vessels tonight as the firefighters needed all the space they could get to stretch out more hoses. Although it appears that four boats are a total loss, the quick actions of the marina harbor staff and first responders prevented further damage and further vessel loss. We are still working with our client’s vessel to determine whether we have a total loss situation or one that can be remedied, however the upside for all… no injuries, only burnt plastic and wood, all of which can be replaced. For the Ox Bow Marina ownership, berthers and residents of Ox Bow, I could think of no better outcome to this serious situation.

As mariners, there is no such thing as being overly concerned with safety measures or being overly prepared to handle an emergency situation. Seek out an annual vessel safety check by a certified vessel safety examiner from the U.S. Power Squadron or the U.S. Coast Guard Auxiliary. The required items under this inspection are the low bar but are a good starting point to help ensure your vessel is safe to operate. My article subject matter is largely focused on safety items and situations of a safety nature for a reason. Be safe on the water and do not become a victim to complacency or neglect.

It is now time to kick back and enjoy a good Port and cigar.

Until next month please keep those letters coming. Have a good story to tell, send me an email patcarson@yachtsmanmagazine.com. I love a good story.