Lessons Learned – by Pat Carson

Rule 14

It was a beautiful Saturday morning in Alameda, and we had planned on a late start for our voyage to the Delta. Departing Richard Boland Yacht Sales’ docks at Marina Village around 1100 in our speedy Riviera 43 convertible would put us comfortably into Willow Berm Marina at approximately 1500, just at high tide. After we passed the no wake zone and Bay Ship drydocks we prepared to pick up our speed and make the best of the sunny day and calm waters. Looking up ahead I could see no less than 20 recreational boats, a ferry and a USCG small boat. The recreational boats were all going every which way with almost no regard to safe seamanship. The USCG small boat was in route to correct one of the errant boaters and the ferry coming down the red side starting to slow for the Alameda ferry landing and were both operating textbook perfect.

I understand vessels wanting to keep their chosen speed and having to maneuver around slower boats, mainly sail, however keeping in mind that the correct side of the channel is the right side.

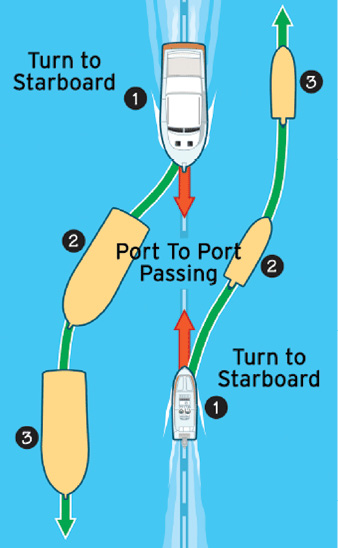

Rule 14 Head-On Situation

(a) When two power-driven vessels are meeting on reciprocal or nearly reciprocal courses so as to involve risk of collision each shall alter her course to starboard so that they shall pass on the port side of each other.

(b) Such a situation shall be deemed to exist when a vessel sees the other ahead or nearly ahead and by night she could see the masthead lights of the other in a line or nearly in a line and/or both sidelights and by day she observes the corresponding aspect of the other vessel.

(c) When a vessel is in any doubt as to whether such a situation exists, she shall assume that it does exist and act accordingly.

The SS Marine Leopard And The SS Howard Olson

The SS Marine Leopard, a 522-foot, single screw ocean freighter, departed Oakland, CA on Sunday evening May 12 with 12,000 tons of cargo enroute to San Pedro, CA. She passed the San Francisco Sea Buoy at 2042 PDT, set her course for 165°T and ordered full ahead steaming at approximately 17 knots. At approximately 2250 and three miles abeam of Pigeon Point light she altered course to 156°T. At 0000 the 3rd mate relieved the watch and continued this heading, making only a small course alteration to avoid a small boat down the coast. During his watch, the 3rd mate was overtaking the SS John B. Waterman who was making 16 knots on the same heading, 156°T. At 0155 the Marine Leopard overtook the John B. Waterman on her starboard side and was 0.6 miles to her starboard and approximately three miles from Point Sur. Just prior to 0200 a white light became visible bearing about one point on the port bow with the RADAR showing a distance of 17 miles. The light was seen visually by the 3rd mate and by the bow lookout who reported the light as dead ahead. Per night orders, the captain was called to the bridge at 0200 and was informed of his vessel’s position, the presence of the John B. Waterman and the approaching vessel which was then estimated at 15 miles distance and one point to port.

At 0202 the captain took over navigation of the ship, disengaged the autopilot and ordered a course change to 150°T. Note that the SS Marine Leopard had just altered her course to the left when she sighted another vessel on her port bow at a distance of 15 miles! The captain continued to observe the approaching Howard Olson which at 0210 was appearing dead ahead, when she was approximately three miles distant, which was confirmed with reports from RADAR and bow lookout and ordered the helmsman to change course to 152°T. At the time of his course change both side lights and the range lights of the Howard Olson were visible. Two minutes later at 0212 the captain ordered another two degrees to the right, and at 0214 ordered another right two degrees bringing her new heading to 156°T. The two vessels were now less than one mile apart.

The SS Howard Olson, a 261-foot, single screw lumber freighter, was enroute from San Pedro, CA to Coos Bay, OR with ballast and was on a course of 320°T making eight knots. At 2200, hugging the coast, she passed Cape San Martin three miles to her starboard as she approached Point Sur. The heading of 320°T was chosen earlier at Point Buchon and she intended another course change at Point Sur depending on weather. At 0140 on May 13, the watch officer spotted lights on her starboard bow on the horizon. These lights later proved to be the John B. Waterman. At the same time the lookout on the starboard bridge wing reported to the 2nd mate another vessel’s white light appeared one point to starboard but further from shore and apparently on a southbound heading. This light later proved to be the SS Marine Leopard. Eight minutes later at 0148 the watch officer reported the Point Sur light at a bow bearing of 005°T. No distance reported as the RADAR was not in operation.

At approximately 0200 the 2nd officer saw the green side light of the Marine Leopard one point to starboard while the range lights and green side light of the John B. Waterman were greater than 30 degrees off the starboard bow. The Howard Olson continued on her heading of 320°T for another 15 minutes until 0215, at which time the two vessels were less than 3.4 miles apart.

At 0200 on May 14 both vessels were approaching Point Sur on nearly reciprocal courses and both had each other’s navigation lights in sight and targeted on RADAR when greater than 10 miles apart. The seas were calm, the weather was clear and dark with excellent visibility. The bridge crews on both vessels had each other under constant observation. This was apparently a normal head-to-head meeting situation and both vessels were expected to alter their courses to starboard and pass, port to port. What the two watch officers did in the last few minutes sealed their fate.

In approaching the Howard Olson, the Marine Leopard changed course from 156°T to 150°T to pass closer to Point Sur, but at the same time closed in on the Howard Olson. With the Marine Leopard now on a course 150°T, the Howard Olson, steady on a course of 320°T and separated by half a mile with a closing speed between the two vessels of 25 knots, changed her course 10 degrees to the left and blew two short blasts of the whistle indicating her intention of a starboard-to-starboard passing. When the Marine Leopard noticed the course change of the Howard Olson, she then changed course to the right. Just before the collision and seeing the red side light of the Marine Leopard the 2nd mate on the Howard Olson ordered engines full astern and full left rudder. A few seconds later the vessels collided, and the bow of the Marine Leopard entered the starboard side of the Howard Olson at an angle of 90 degrees. The Howard Olson took a severe list, her bow broke off and the vessel sank. Her crew jumped into the water in a position approximately four miles off Point Sur. The captain of the Howard Olson was awakened by the ship’s whistle, and seeing the lights of the Marine Leopard in his porthole ran to the bridge just in time to witness the collision. At the time of the collision, the captain on the Marine Leopard sounded the general alarm, ordered engines full astern and then directed the 3rd mate to his lifeboat station. At the direction of the chief mate, the lifeboat crew got into the boat and was lowered and waterborne and away at 0223.

The motor lifeboat from the Marine Leopard circled around and passed the floating bow section of the Howard Olson into the debris field picking up survivors. The 3rd mate and his crew picked up 23 oil covered survivors in 45 minutes and then returned to the Marine Leopard. The Marine Leopard’s other motor lifeboat was in the area as well as a lifeboat from the John B. Waterman which was less than one mile away at the time of the collision, and had stopped to assist upon hearing and seeing the collision. Three survivors were picked up by the Marine Leopard’s second lifeboat and two by the John B. Waterman’s lifeboat. While the lifeboats were being lowered on the Marine Leopard, the captain notified the U.S. Coast Guard Sector San Francisco and the survivors were later transferred to a USCG cutter and taken to Monterey where they received medical attention. One survivor was taken ashore by USCG helicopter.

Three of the Howard Olson crew did not survive and one member was neither seen nor recovered. The Howard Olson was a total loss. The damage to the Marine Leopard consisted of damaged plates to both sides of the vessel’s bow, above and below the waterline, as well as loss of the starboard anchor.

USCG Marine Board Of Investigation

It was the opinion of the board that the two vessels were meeting on a head to head situation under Rule 14 of the COLREG’s, and the presence of the John B. Waterman did not bring the case within the rule of special circumstances because the mate on watch on the Howard Olson stated that he was not concerned with the presence of the Waterman. The mate on the Howard Olson violated Rule 14 of the international rules for not changing his course to starboard to make a port-to-port passing, and the captain on the Marine Leopard violated the international rules for not blowing his whistle when making course changes to starboard.

The board considered that the actions of both the captain of the Marine Leopard and the second mate on the Howard Olson warrant not only action for negligence but also in view of the loss of life such action as found necessary by the U.S. Attorney General for criminal negligence. They further recommended that suspension and revocation proceedings be instituted against the licenses of the captain of the Marine Leopard and the second mate of the Howard Olson.

After reading recount what other rules did the respective bridge officers fail to consider and violate? There are many.

Lessons Learned

For most, boating is recreation; our time on the water should be as stress free as possible. For those that are new to operating a power-driven vessel, Rule 14 is actually easy to remember. Just as you are driving a car down a narrow lane and another vehicle is approaching from the opposite direction, you naturally move as far right as you can, usually slowing to pass the other vehicle port-to-port. When navigating the narrow sloughs or rivers of the Delta, or any of our waterways, keep Rule 14 in mind and keep to the right side of the channel. Don’t forget to watch the depths on your sounder and use your local knowledge of the channels. For those that have taken the California boating card class, 35 years old and under this year, the steering and sailing rules are covered. You should be familiar with Section II – Conduct of Vessels in Sight of one another and specifically rules 13, 14, and 15.

Until next month, please keep those letters coming.

If you have thoughts on the other rules violated in this collision story, please write.

Have a good story to tell, send me an email. patcarson@yachtsman magazine.com.

I love a good story.