Lessons Learned – by Pat Carson

Bilge Pumps

While on a boat delivery a few years ago we were navigating a 48-foot sportfish convertible from the San Juan Islands to San Francisco. After a particularly difficult 30 hours in rough seas we decided to make landfall in Astoria, Oregon to take on fuel and other supplies and let the seas calm. Prior to fueling the vessel, we had docked at an end tie. While walking down the dock we got a good view of the vessel from the side and noticed that the stern was looking pretty low. It seemed odd at the time because we had transferred all 600 gallons of fuel from the aft tank during the voyage, and the only items in the lazarette were the fuel tank and some storage for lines and fenders. Our last five hours of running had been in rather large following seas that did occasionally spill water into the cockpit. I did not think much about this since the boat was designed for these conditions and fitted with giant scuppers in the cockpit and watertight lazarette hatch seals. Water pooping the cockpit was simply an issue I had not considered as a problem. When I opened the lazarette hatch and found the bilge almost completely flooded, I understood why she was trimmed low in the stern. But what I did not understand is why the bilge pumps were not extracting the water.

Two days before getting underway we tested all the bilge pumps and they worked as expected, however this one appeared now to not work. A quick check of the pump circuit breaker and all looks good, so we activated the pump manually. The pump immediately comes to life and in less than 20 minutes the lazarette is emptied of several thousand pounds of seawater. The pump works fine but apparently the automatic float switch does not. As we are pulling all the spare fenders and lines from the lazarette I remember that this boat has the electronic water sensor float switches and not the more common mechanical ones. When we inspected the dewatering systems prior to getting underway we checked all the bilge pumps for proper operation, and they all did, however we only checked the manual switch and not the automatic float switch. The mechanical float switches are easy to test, just reach down and lift the float or rotate the test knob and the bilge pump should immediately come on. The electronic water sensors cannot be tested this way. The combination of a defective hatch gasket that allowed water from the cockpit to leak into the lazarette, a defective water sensor and heavy sea conditions allowed several hundred gallons of water to weigh down the stern. Seawater weighs approximately 8.6 pounds per gallon, so our several hundred gallons of seawater added somewhere around 2,000 pounds to the aft end. While most recreational boats have a common bilge where water can move between the spaces, the design of this boat has three separate watertight bilge spaces with no water movement between them. Water in the lazarette stays there and will not move to the other spaces where the other bilge pumps can take care of it. These are design tradeoffs and one of them is that pumps in other bilge spaces won’t pump this space free if it floods, but the water in this space stays there. Even with complete flooding of the space the vessel will not sink. A high-water alarm with a second pump in this space, similar to the vessel’s setup in the engine room, would be a nice addition.

Check, Check, Check

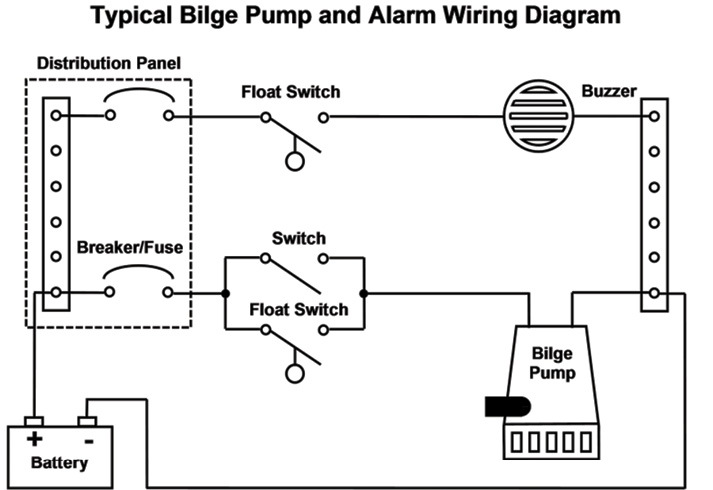

The automatic bilge pump switch sits low down in the bilge among sloshing seawater, oil and other debris, and is expected to function at a moment’s notice. Its purpose is simple; switch on the pump when the water in the bilge reaches a predetermined level and then turn off the pump when the bilge is dry. Seems simple. So why are there so many different variations of switches and pumps available? And why don’t they always work?

Prior to taking a boat on a coastal voyage we have a pretty extensive checklist to go through and that list includes operating all bilge pumps, both manually and automatically and observing the indicator lamps to be certain a visual warning is provided that a pump has activated. We test the high-water alarms to be certain there is audible indication of high water in the bilge and check to see if the high-water pump activates. I do occasionally find electronic float switches and have yet to find a way to test them, so we just test the manual functions of the pumps and alarms for proper operation. This is the first time I have found an apparent faulty electronic water sensor, and there rests the problem; you may not know the sensor is faulty until it is too late and the bilges fill with water.

Float Switch

Bilge pump float switches come in three basic categories: the common pivoting arm, the vertical float and the electronic sensor.

The pivoting arm is by far the most common and easiest to test. Simply lift the float and see if the pump comes on. The major complaint of this switch is that it can easily be fouled, preventing it from rising with the water and activate the pump if something gets on top of it, or fails to lower and shut off the pump if something gets under it. Newer versions of this old standby have a guard cage around the pivoting arm float to prevent fouling and have a test knob to easily lift the float.

Personally, I prefer the old Rule 37 pivoting arm float switch; they are very simple and over the years have proven to be very reliable. They are easy to test and you can also see visually if the float has lifted with the water. Have you ever seen a float switch so low down in the bilge that you cannot get to it? Or do not feel like crawling around to test the switch? With the old Rule 37 I have many times taken my boat hook and from a comfortable distance, reached down and lifted the float to check the pump operation. You cannot do that with any of the other styles.

The vertical float switch has a small float with a magnet mounted on it and placed inside a sealed chamber that lifts as the water rises. When the float reaches the top of the chamber the magnet activates a reed switch, which in turn activates the pump. Some, but not all of these style switches have an external test lever for manually lifting the float and activating the pump. One advantage of this type of switch over the pivoting arm is that it is less prone to activating with sloshing water since a several second delay is built into the mechanism.

They are about the same cost as the pivoting arm switch, are said to be more reliable and offer less pump cycling. If you decide on this style be certain to select a version that has an external test lever.

The electronic switches use one of two technologies: Capacitive Detection or Mirus Field Effect. The claimed advantage to these switches is that they can detect the presence of oil, diesel, coolant or gasoline, and will not activate if any of these are present. I can see advantages and disadvantages to this design. For routine evacuation of bilge water it is good to prevent hydrocarbons from being pumped into the environment, but on the other hand if your boat is flooding and the only thing between you and going for an unplanned swim is the bilge pump, I would rather worry about oily bilge water being pumped overboard later, when I’m at the dock and dry. I know of no way to test the function of these switches short of filling the bilge with water and seeing if the pump activates.

A design that has two large bilge pumps with two independent float switches and the common old pivoting arm float switches would be a good setup for just about any vessel. Water will lift the lower float switch and activate the first pump.

If that main pump cannot keep up with the water intrusion and the level keeps rising, the second float switch is lifted and activates the second pump. Also attached to the second and higher mounted float switch is an audible high-water alarm to warn the operator that something is seriously amiss in the bilge. This system is easy to test, simple in design and provides a level of redundancy. The only particulars I would do different would be to add a hydrocarbon filter to the first pump and make the second pump much larger.

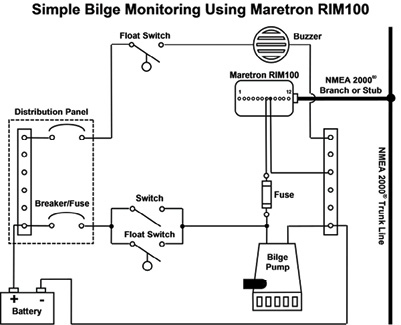

Bilge Monitoring, A Better Way

In a typical bilge pump system there are two ways for the bilge pump to be activated: manually or by the automatic float switch. When water rises to a preset level, the float switch will allow battery voltage to be applied to the pump and it pumps the water from the space. The manual switch overrides the automatic switch and allows the pump to be turned on at any time. Ideally the system has a second automatic float switch mounted a bit higher than the first, and is connected to an alarm that will sound if water continues to rise above the first automatic switch.

A more modern design uses a NEMA2000 interface module such as the Maretron Run Indicator Module. In this design, anytime voltage is applied to the pump, whether automatically or manually, the RIM will send a signal over the NEMA Network indicating that the pump has been energized. This system allows you to understand what is happening down low in the bilge as you now have information as to how often the pump activates and how long it runs.

Lessons Learned

Your vessel’s bilge pumps are the first line of defense to prevent sinking. They do routinely clear incidental water from the bilge. However if the worst occurs, they will give the crew extra time when the vessel is taking on water. Time can make the difference from making it back to the dock or going for an unplanned swim. This extra time can also be spent repairing the leak, putting on floatation or making a distress call on the VHF radio. Properly operating bilge pumps can be immensely valuable in an emergency as long as they are properly installed, properly maintained and in working condition. This is not an area to scrimp and try to save a few bucks. No matter the brand of pump or automatic float switch installed on your vessel, be sure to test them regularly for proper operation.

What can we learn from these experiences? Often neglected bilge pumps are one of the more critical systems in a boat, and should be inspected for proper operation at regular intervals. While even the largest of pumps will not necessarily keep your boat floating if you put a hole in it, they may buy you enough time to find the cause of the water intrusion and stop the flooding. In my Lessons Learned situation, I had checked the pump operation by activating the manual switch at the helm station and observed the indicator light showing the pump was activated. What we could not check was the automatic function because of the electronic automatic switches. I do not have a good solution to this problem. If you do, please send me a message.

Recently on a vessel I observed the use of household style wire nuts to connect wires to the bilge pump. Not only are these connectors designed to be used with solid copper wire only (not stranded wire), they WILL vibrate loose and are not moisture proof. Using these to connect a bilge pump is just asking for problems. Never ever use wire nuts for any electrical connection on a boat. Of course, they got changed to proper connectors.

It is now time to kick back and enjoy a good port and cigar while I watch and wait for water to enter my bilge so I can observe my pumps doing their job. Kind of like watching grass grow, but anything you do on a boat with a cigar and glass of port is more fun on the water than it is on land.

Until next month, please keep those letters coming. Have a good story to tell, send me an email patcarson@yachtsmanmagazine.com. I love a good story.